follow us

Search this site

| contribute | advertise |

| terms of use |

© 2025 Mambaonline cc

| Lesbian South Africa |

| Lifestyle | News |

Interview: Zanele Muholi Ė Making the invisible visible

02 October 2016

Zanele Muholi (pic: David Penney)

Her work has both been lauded, winning many international awards, and condemned (in 2010, South Africaís Arts and Culture Minister Lulu Xingwana stormed out of an exhibition featuring Muholiís images of women embracing, describing them as ďpornographicĒ).

She was a journalist and photographer for the groundbreaking but now sadly closed Behind the Mask LGBT website and was one of the founding members of the activist group FEW (Forum for the Empowerment of Women). Muholi has gone on to lecture around the world, launched the Inkanyiso visual activism organisation and even mentored some of the women sheís photographed to become photographers in their own right.

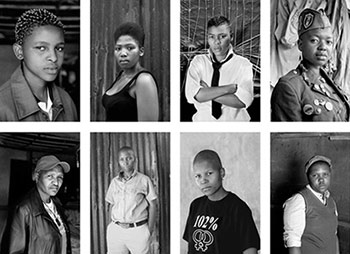

Amongst her most iconic projects is the Faces and Phases series, for which, since 2006, she has produced around 250 portraits of lesbian and transgender Africans. The black and white images are aimed, Muholi says, to make visible ďan often invisible community for posterityĒ.

It is a community that has been at the front line of the brutal and often deadly war against LGBT people in South Africa. As opposed to the all too common depiction of these women as victims, Muholiís participants (she does not see them as passive subjects) exude strength, pride and power.

Faces and Phases is an important artistic and socio-political project that she continues to work on today. As the iconic series recently celebrated its tenth anniversary with an exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg, Mambaonlineís Luiz De Barros spoke to Muholi about the project and what drives her almost obsessive need to document those around her.

Did you ever imagine that youíd be spending 10 years working on Faces and Phases?

Not really! I just took on the project as part of my life, and considering that we lost a lot people along the way, one couldnít imagine that. So, for me this is a milestone; just like we have won most of the queer milestones in this country; ranging from the Civil Union Act of 2006 to the Constitution of 1996 to the youth of 1976 to the women of 1956. I didnít know that it would go this far. All I knew is that this is my responsibility. I have a task at hand; I have to work.

You mentioned that we lost a lot of peopleÖ

You know, people have been killed and weíve taken a lot of risks in life, including you and including myself. A lot of people have been killed. We have buried a number of people, we have attended a lot of hate-crime cases where weíve supported the families of the dead lesbians, the dead gay men, the dead trans people in this country. So much has happened, we canít just move along as if weíre immune. You know, Iím living on the edge and anything is prone to happen. But then through the grace of the Almighty we are still here. Weíve also lost a lot of our people from chronic illnesses; weíve lost a lot of our people from HIV complications etcÖ

Do you think youíve almost felt a sense of urgency to capture them?

Itís very important to say and mention, as a person who works in media, as yourself whoís running media, whoís been writing media for long. Weíre not visible enough, we are not visible enough. We have not made it in any mainstream magazines, as much as Iíd like us to. Often, when you have images of lesbians in the mainstream, itís about hate crime, itís about dead lesbians, itís about tragedy. And itís very rare that you find the black lesbian aesthetic; maybe with the gay boys itís different! But with black lesbians Ė give us a True Love cover. How is it that weíre not there? We consume such magazines. I buy them too. So for me, this is my responsibility, more than anything else. Faces and Phases is a life-long project.

In terms of the participants in your series, how do you find them? Are they people that you know in your life, people that you come across, do you specifically go out to find them?

No, I donít look for people. People are alreadyÖout there! One of the major things for any person whoís in my series: you need to be out, you need to know who you are, and you need to be of the age of consent. People who are featuring in Faces and Phases are friends and friends of friends and fellow activists and people that are regarded persons and that are recognised for their work in different ways. And I prefer to work with people that I know, than to work with strangers, and in that way itís safer and people know who am I. And people are okay that they shall be seen. So no closeted kinda individuals needed for this series, ícause we are all taking risks!

Faces & Phases (Zanele Muholi)

Visibility for LGBTI people should be like Ö food and water! Should be things that we cannot bear to live without! So, if weíre not visible enough, it will mean that we are failing ourselves. And it means not only visible in certain spaces but all over. We canít only be visible when itís Pride because we donít live our lives for just one day of the year. We exist 365 days, throughout the whole year! And this visibility needs not even to be negotiated; it needs to be part of the society. And let people out there who do not want to understand get that we deserve to be respected and recognised. And also to be written in history, and also not to have this visual history be limited to certain number of individuals. But we just need to be practical about it and ensure that our people are safe, because not only do you become visible but you are at risk of being violated.

From what I understand, youíve gone back to some of the participants in your series and you started photographing them again. Why did you decide to do that?

Remember that most of the work that I do is more about relationships. Iím not doing an assignment, assigned by some press. Iím doing this passionately; Iím interested in the people that I photograph. I like the people that I photograph, so to maintain that relationship that is already established is key to me. So I want to know what is going on in peopleís lives: where theyíre at in terms of progress, and where can I, or how can I intervene, wherever possible. So it canít just be a once-off thing, which is why itís very, very important for me to always go back and forth. Sometimes it takes years Ė not only just one year apart. Other people are photographed maybe in 2010 and I went back to them six years later. Other people I photographed them two years ago and Iím back at them now.

In terms of your upbringingÖ What was it like? Was it welcoming to lesbian women?

I donít know if you have seen my documentary Difficult Love, where Iím in conversation with my family members and so onÖ My family is okay with me. I donít need to try hard. The surroundings where I grew up? I didnít see many people who were visibly out as LGBTI. There were a few individuals that I was close to, but in terms of having documentation that really helped one to be fully comfortable, that was something else. The space in which I lived I didnít project as much as when I came to Johannesburg, because we didnít have a Johannesburg Pride. My familyís okay about me being me Ďcause I think Iím a responsible being and I do things right and donít need to hide myself or hide my sexuality to them.

Did you ever have a coming out experience to your family?

For most of us thereís no coming out session where you have to bring your grandfather, your grandmother Ö people are dealing with hectic issues, you know! Coming out was never a planned thing. I never had to say Iím sitting my mother down. I lost my father when I was a couple of months old so I never met him. And then I grew up with my Mom and grandfather. But I didnít have to sit down and discuss anything. My Mom just sorted out issues and made sure that I was comfortable with everybody in the house. So everybody knows. Everybody knows.

So would you bring a female partner to the family?

Oh, definitely! I have had girlfriends. Every December, I take my crew and some of my friends to Durban Ė thatís where we spend Christmas and New Year in Durban as a unit. And there nobodyís judged or undermined in any way.

Picture you at 15. What kind of teen was Zanele at that age?

[Laughs] I was an ugly girl, who was forced to wear dresses. Iíll send you my picture when I was six. That was just a boy in a dress! And I like that photograph because it kinda makes you realise the importance of photography and documentation and I appreciate it much more than ever before. At 15, I just had issues and wanted to be out of high school and leave Durban and be in a different space. At 16, I came out to myself. Like there are moments you come out to others but there are moments where you come out to you. So 16 was when I came out to me! And accepting the fact that I was an important person to me and recognising the person that I was and the person that I am. So I didnít need anybodyís validation. I was a struggling teenager dealing with so many things, but one had to survive. At 17, I completed matric. I spent one year, aged 18, working at a factory in Durban, at 19, I was in Johannesburg. So, Iím in Jozi now, Iíve been here forever.

Were you ever subjected to bullying because of your sexuality when you were a kid and when you were growing up?

I mean, bullying got kinda like a different thing. The bullying of the 90ís and the bullying of the millennium is different. And how also youngsters deal with it and how they are negotiating their spaces and how their teachers force this bullying even further to kids that are different. Bullying happens every day Ė not only at school, at churches bullying is what we call homophobia hate-speech, verbal abuse. Itís been there, now somebody from somewhere decided to use the word bullying. Thatís verbal abuse, thatís homophobia. Weíve been there, weíve been thereÖ

Zanele Muholi (pic: David Penney)

I want to be seen as Zanele Muholi. I donít want to be a role model Ė I want to be a human being living with other human beings. I want people to have hope and know what I am doing is possible. I want people to get as much support as possible from me. But I donít want to be an exception, I donít want to be anything thatís extraordinary! I mean come-on Luiz youíre doing it too! I donít know if you also see yourself as that? I just want to be me, living in the world making a difference!

I think the motivation is not to be a role model, but I think it is important to have visible people Ö.

Sure, I get that! But that response will come from other people. It will be people who will say that you are a celebrity, it will be people who say that you are a role model.

What is Zanele like when sheís not working? What does she like to do? What is your downtime?

My downtime is when Iím not working. Photography has become my fix! And I spend time with people that I love. I like hanging around, but Iím not for the bars and stuff Ė I donít drink and I donít smoke, so Iím boring. So I work most of the time, I work. And I like to travel, so I travel a lot. Then itís nice and also not like on vacation, ícause I cannot afford more. So I travel and explore different spaces where Iím there either to exhibit or give advice.

Okay, my final question. We talked about Zanele when she was 15. Describe Zanele today. What kind of woman is she?

Iíd say Iím just a human being living in the world Ė passionate about photography, pushing the visual activism in ways that I know how to, thatís what makes me happy. Iím working towards two publications that will come out next year. Itís just work, work, work Ė that Rihanna! [Laughs]. No, Iím working because everybodyís working, so thereís no time to slow down. Thereís a lot that still needs to be done. We havenít reached any end really!

Faces and Phases 10 is on at the Stevenson Gallery (62 Juta Street, Braamfontein) until 14 October.

Luiz DeBarros

-

3 - 3

-

3 - 3